When it comes to reporting about sexual violence, the media in Uganda is misleading at best and a catalyst for further violence at worst. Global women’s movements have accused the media of using language that trivializes the experiences of the survivors and publishing unverified/untrue information about survivors. In addition, reporters have been known to ask the most invasive questions they can think of, use survivors’ images without consent and paint them as malicious accusers who are masterminding schemes to destroy men’s reputations. Violence against women is rarely presented as the systemic issue that it is, hinged on patriarchal norms and attitudes. This is dangerous because the media plays a critical role in transforming societal norms and its coverage of crimes, including sexual assault, has an impact on the knowledge, beliefs, attitudes and behaviors of the public.

For this reason, Akina Mama wa Afrika in partnership with Hivos hosted a webinar on March 28, 2020 from 11AM-1PM EAT on sexual harassment and the media. The webinar was attended by fifty-five (55) people from across the globe. The purpose of this conversation was, first to assess the prevalence of sexual harassment in the sector, secondly, to interrogate media’s documentation and reporting of cases of sexual harassment while thirdly, suggesting new feminist alternatives in order to further the larger cause of stopping sexual harassment in the world of work and beyond.

The panel was comprised of; Lydia Namubiru, a Ugandan feminist, investigative data journalist and researcher who is currently the Africa editor for openDemocracy 50.50. Kiki Mordi, an award winning investigative Nigerian journalist, famous for the BBC Africa Eye documentary #SexForGrades exposing the sexual violence in universities in Nigeria and Ghana and Alice McCool an independent journalist and producer whose story exposed the sexual violence girls in Kalangala district suffered at the hands of Bernhard Glaser, a German national accused of sexually assaulting children in the children’s home he was running. The webinar was moderated by Jacky Kemigisa, a feminist researcher and journalist. She opened by situating the conversation in the context of the history of the #MeToo Movement and crediting its founder Tarana Burke- the Black woman activist who started it in 2006. She highlighted that the movement and hashtag which has now exploded into the mainstream with the conviction of disgraced Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein was created to allow women to share their experiences of sexual violence and to show how pervasive it is.

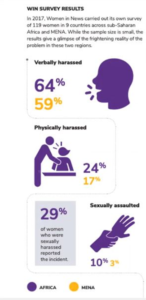

She invited Alice who started by sharing three illustrations by Ugandan illustrator Charity Natukunda that accompanied the aforementioned story of sexual violence in Kalangala. These pictures, she said, depict the power dynamics at play, the abuse and the resistance by the survivors. Lydia joined the conversation to share a picture of statistics from a Women in News 2017 survey across nine countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (see below).

She explained that these findings are not unusual or unbelievable. The numbers are not surprising because, sexual harassment is normative in the world of work and the media industry is not exempt. “Prevalence of sexual harassment in media organizations is hardly studied. Employers hardly pay attention or study the extent to which sexual harassment occurs in their work places. In that official obscurity a culture thrives so it is hard to come across data that tells you how big a problem it is” she said; adding that the way violence is dealt with internally by media organizations informs how these stories are covered because it influences how both victims and perpetrators are seen and presented.

Kiki Mordi shared her experiences investigating and reporting stories of sexual harassment at universities in Ghana and Nigeria in her #SexForGrades documentary. She explained that the focus of sexual violence reporting is usually the victims/survivors and the #SexForGrades documentary wanted to focus the camera on the abusers.

The way we report sexual harassment focuses too much on the victim and not enough on the perpetrator. It is high time as a continent that we transfer the shame we feel as victims/survivors to the perpetrators because if a person steals and they are caught, they feel shame but somehow when it is rape, it is the victim who feels ashamed. It does not make any sense… -Kiki Mordi

She emphasized the importance of protecting victims from further harm even if they are brave enough to stand in front of the camera because there are punishments inflicted on women who speak up. Since the documentary, Kiki herself has been the recipient of hate mail from people who say she is ruining the reputation of the continent. She recommended that reporters be mindful of where they are steering the conversation and ask themselves if it is being steered towards victim blaming or accountability for the abusers.

“The experience of investigating #SexForGrades was humbling. Everyone who wore the mask was heroic. They were human beings and not just journalists and understood the responsibility that the documentary had potential to create a cultural shift and huge change in how sexual harassment is seen in Africa” -Kiki Mordi

Lydia continued from Kiki’s presentation by reiterating that the thing that is missing in the way media covers sexual harassment stories is, humanity.

There is so little humanity in the media coverage of sexual violence which is very odd because journalists, are of course human beings. Nobody asks you to split your humanity from your journalism… However, the systemic bias towards women does not allow for the same humanity that would be used to cover a story on poverty or political violence to be present in covering stories of sexual violence” -Lydia Namubiru

The panelists proposed a list of good practices to take into account when interviewing survivors or while writing stories on sexual violence and shared some recommendations for media organizations which you can read here. Alice called on journalists to examine their privileged positions of power particularly when reporting on issues of sexual violence and other sensitive gender issues.

We must center the voices of the survivors we interview and be prepared to learn from them and as feminist journalists, our work must be inclusive of all women…Media reporting has great potential to bring about positive change but also great potential to cause a lot of harm. -Alice McCool

In her concluding remarks, Leah Eryenyu, our Advocacy and Movement Building Manager, mentioned that media houses and even Civil Society Organizations could benefit from the wisdom shared and recommendations given about telling stories with sympathy so that survivors are treated as human beings, an aspect which has been missing. The way media covers/reports sexual violence is a reflection of the society which still largely downplays stories of women. This conversation was a starting point on how not just journalists but story tellers, media organizations, audiences and society at large can do better by and for survivors.

We shall never treat sexual violence survivors well enough if we do not recognize the extent to which they are us. They are very much like us; their experiences are very much like our own…”-Lydia Namubiru